Just like in SWT, you can also create custom widgets to extend the RAP widget set to your needs. Examples range from simple Web2.0 mashups to complex widgets such as custom tab folders, or widgets that display graphs and charts.

There are different types of custom widgets which will be described below. But no matter which type of custom widget you implement, you will end up with an SWT widget that has an SWT-like API and inherits some methods from an SWT super class. Therefore you should make yourself familiar with some important rules of SWT before you get started. We highly recommend to read this article by the creators of SWT:

These types differ a lot with regard to the features they support, the dependency on a certain platform, and also the effort it takes to create them.

These are the simplest ones.

Compound widgets are compositions of existing SWT widgets.

These widgets have to extend Composite.

There is no difference between SWT and RAP for compound widgets.

Everything that is said about compound widgets in [1] also applies to RAP.

Writing a compound widget does not require any JavaScript knowledge. The widgets are re-usable in desktop applications with SWT.

These are also simple.

Sometimes you might want to need a widget that draws itself.

This can be done by extending Canvas.

The canvas widget supports drawing in a paint listener.

For writing this kind of widgets, you can also follow [1].

Please note that the drawing capabilities of RAP are limited compared to SWT.

Especially in Internet Explorer browsers, the performance degrades with the number of drawing

operations.

Writing a canvas widget does not require any JavaScript knowledge. The widgets are re-usable in desktop applications with SWT.

These are still rather simple.

The SWT Browser widget lets you place any HTML into your application.

In RAP, this is no different.

Any JavaScript code placed in a Browser widget will end up in an IFrame element.

This makes it easy to wrap Web2.0 mashups or include existing components from other JavaScript

libraries.

Using the SWT BrowserFunction API, you can even send events from the JavaScript

code that runs in the browser to the Java code of your widget.

Remember not to subclass Browser but extend Composite instead and

wrap the Browser widget.

This way, you do not expose the API of the Browser to user of your widget, but instead provide

an API that is specific for your widget.

A good example of a “mashup” custom widget for Google Maps can be found in [2]. Another example [3] shows how to include a JQuery UI widget into a browser-based custom widget.

Just like in SWT, writing real native custom widgets is hard. You need deep knowledge of both RAP and the platform you are developing for, i.e. the browser and any libraries you use. You have to know the JavaScript library of RAP, the communication between client and server, the request lifecycle, and life cycle adapters. Luckily, you get around writing native custom widgets most of the time by using one of the above solutions. Future versions of RAP will simplify the writing of native custom widgets.

Native custom widgets are not re-usable on the desktop unless a specific desktop version is being developed.

A RAP widget consists of a client part and a server part. Both parts have to be synchronized. There are different tasks to create a new custom widget which will be covered here:

As an exemplary widget we will implement a native Google maps widget.

You can find the example code for this widget in the RAP CVS:

dev.eclipse.org/cvsroot/rt/org.eclipse.rap/sandbox/org.eclipse.rap.demo.gmaps

Note: this example is here for historical reasons, today you could do the same using the Browser widget as shown in [2].

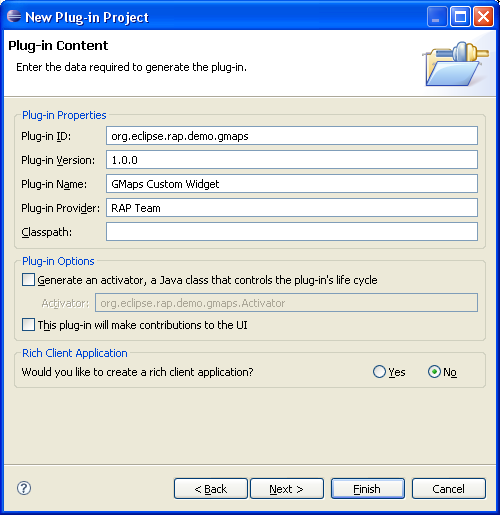

To have a clear line between your application and your widgets we'll create a new plug-in

project called org.eclipse.rap.demo.gmaps. We don't need any additional

aspects like an RCP application or an activator.

The first step is to create a java class - the widget itself - to talk to the developer like

every other widget. In our case we will call it GMap.java in place it into the

org.eclipse.rap.gmaps package. As super class we use org.eclipse.swt.widgets.Composite

to have to have a proper base class which interacts with the rest of SWT. To store the address which

will be shown on the map, we create a new field in the GMap class called address

and will generate the corresponding setter and getter. The setter - setAdress( String ) - should

check for null values and replacing null with an empty string instead. It

should look like this in the end:

public void setAddress( String address ) {

if( address == null ) {

this.address = "";

} else {

this.address = address;

}

}

To have an example for the other way around - from client to server - we introduce another

field called centerLocation to get the current location of the map when the

user moves it around. This is done by adding a new field to the class together with its

getter and setter:

private String centerLocation;

public void setCenterLocation( String location ) {

this.centerLocation = location;

}

public String getCenterLocation() {

return this.centerLocation;

}

Additionally we override the setLayout(Layout) method of Composite

with an empty method as our custom widget does not contain any other widgets.

That's all for now - this is all needed by the developers who want to use our the custom widget.

Now it gets interesting as we have to work out the JavaScript side of our widget.

On the client side our widget is just a JavaScript class defined with the

qooxdoo syntax.

As super class we need to use at least

qx.ui.core.Widget.

To have an easier life we will directly use one of the

qooxdoo layout managers

as base of our widget. The code for the new qooxdoo class together with qooxdoo's

CanvasLayout as super class will look like this:

qx.Class.define( "org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.GMap", {

extend: qx.ui.layout.CanvasLayout,

// ...

} );

The first thing we need to create is the constructor for that class in order to initialize our widget properly.

As parameter we have an id which will be passed to the widget by us in a later step.

The first line is a base call which is the same as super in a java environment.

For now we populate the id to the browsers DOM by adding a new HTML attribute with setHtmlAttribute.

You see some Google Maps-specific calls here which are just there to initialize the Google Maps

subsystem. See the

Google Maps API Documentation

for more information.

The two event listeners for the

qooxdoo widget will take care for the size calculations. This means that whenever the server

sets a new size for the widget we care about our widget to lay out everything inside

(in this case the map) correctly.

The called method _doResize will be implemented later.

qx.Class.define( "org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.GMap", {

extend: qx.ui.layout.CanvasLayout,

construct: function( id ) {

this.base( arguments );

this.setHtmlAttribute( "id", id );

this._id = id;

this._map = null;

if( GBrowserIsCompatible() ) {

this._geocoder = new GClientGeocoder();

this.addEventListener( "changeHeight", this._doResize, this );

this.addEventListener( "changeWidth", this._doResize, this );

}

}

} );

To save the address of the widget somewhere we use the property system of qooxdoo. Adding a new property will look like this:

qx.Class.define( "org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.GMap", {

extend: qx.ui.layout.CanvasLayout,

construct: function( id ) {

// ...

}, // <-- comma added, see JavaScript syntax reference

properties : {

address : {

init : "",

apply : "load"

}

}

}

} );

Qooxdoo will automatically generate the corresponding setter and getter at runtime for us.

So if we want to read the current address of our client-side widget we just need to call

getAdress on a our client-side GMap object. As you see in the apply attribute

of your address property the method load will be called when the value of the

property changes. So let's implement it:

qx.Class.define( "org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.GMap", {

extend: qx.ui.layout.CanvasLayout,

construct: function( id ) {

// ...

},

properties : {

// ...

}, // <-- comma added, see JavaScript syntax reference

members : {

_doActivate : function() {

var shell = null;

var parent = this.getParent();

while( shell == null && parent != null ) {

if( parent.classname == "org.eclipse.swt.widgets.Shell" ) {

shell = parent;

}

parent = parent.getParent();

}

if( shell != null ) {

shell.setActiveChild( this );

}

},

load : function() {

var current = this.getAddress();

if( GBrowserIsCompatible() && current != null && current != "" ) {

qx.ui.core.Widget.flushGlobalQueues();

if( this._map == null ) {

this._map = new GMap2( document.getElementById( this._id ) );

this._map.addControl( new GSmallMapControl() );

this._map.addControl( new GMapTypeControl() );

GEvent.bind( this._map, "click", this, this._doActivate );

GEvent.bind( this._map, "moveend", this, this._onMapMove );

}

var map = this._map;

map.clearOverlays();

this._geocoder.getLatLng(

current,

function( point ) {

if( !point ) {

alert( "'" + current + "' not found" );

} else {

map.setCenter( point, 13 );

var marker = new GMarker( point );

map.addOverlay( marker );

marker.openInfoWindowHtml( current );

}

}

);

}

},

_onMapMove : function() {

if( !org_eclipse_rap_rwt_EventUtil_suspend ) {

var wm = org.eclipse.swt.WidgetManager.getInstance();

var gmapId = wm.findIdByWidget( this );

var center = this._map.getCenter().toString();

var req = org.eclipse.swt.Request.getInstance();

req.addParameter( gmapId + ".centerLocation", center );

}

},

_doResize : function() {

qx.ui.core.Widget.flushGlobalQueues();

if( this._map != null ) {

this._map.checkResize();

}

}

}

} );

There is a little hack involved which is easily explained. We need to listen to click

events in the map and connect them with our _doActivate method to activate

the current shell. This is needed because Google Maps API is implemented with an IFrame

and current browser generations send events only to their document. The IFrame is handled

as a separate document and thus we cannot catch the events to let the shell be activated with

the standard mechanism. This is obsolete for custom widgets without IFrames.

The other event listener for the moveend event will trigger a function to send

the current location of the map to the server. Therefore we need to get the Id - which is

allocated by RAP - of the current widget and obtained via the WidgetManager on the client side.

Then we use the current Request object to add a new parameter which will be

processed later at the server side. If you want to immediately send the parameter to the server

use req.send(). But as we don't need this for now we just add the parameter

to the request object and it will be transfered automatically to the server with the next request.

Ok, we're almost done with our client-side implementation. But the key part of the whole widget is still missing: the piece between the server and the client.

Note: Although the RAP client is derived from qooxdoo 0.7, it does not contain the same classes as the original qooxdoo 0.7 library. It was heavily stripped down and adapted. Therefore you should not rely on the qooxdoo documentation and should avoid using other classes from qooxdoo than Terminator, CanvasLayout, the event system and the RWT classes required for communicating with the server. Future versions of RAP will provide a stable API for custom widget development.

In our current situation we have already done two important tasks: the server- and the client-side widget. Now we need to connect each other in order to control the widget on the client by calling it on the server (where our application lives). In RAP - more precisely in RWT - we have a concept called the life cycle. With each request from the client the life cycle on the server side will be executed. It is responsible to process all changes and events from the client and in the end it will send back a response to the client what to do (mostly hide/show widgets, update data, etc). The life cycle itself is split up in several phases which are executed in a specific order.

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| ReadData | This is responsible to read the values sent from the client like occurred events. At the end of this phase, all widget attributes are in sync again with the values on the client. The attributes are preserved for later use. |

| ProcessAction | ProcessAction is responsible for dispatching the events to the widgets. Attributes may change in this phase as a response for the events. |

| Render | At the end of the lifecycle every change will be rendered to the client. Be aware that only values which are different than there preserved ones are send to the client (means: only the delta). |

To participate in the life cycle - what is what we want to do with our custom widget -

we need to provide a Life Cycle Adapter (LCA). There are two ways to connect the LCA

with our widget. On the one hand side we can return it directly when someone asks our widget

with getAdapter to provide an LCA. This can be done by implementing the

getAdapter method in our own widget like this:

...

public Object getAdapter( Class adapter ) {

Object result;

if( adapter == ILifeCycleAdapter.class ) {

result = new MyCustomWidgetLCA(); // extends AbstractWidgetLCA

} else {

result = super.getAdapter( adapter );

}

return result;

}

...

The preferred way is to let RAP do this itself by creating the LCA class in a

package called <widgetpackage>.internal.<widgetname>kit.<widgetname>LCA.

The order of the internal does not play the big role. The important thing is

to have internal in the package name, the package with the LCA is called

<widgetname>kit and the LCA itself is called <widgetname>LCA.

Here a little example:

If our widget is named org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.GMap,

then our LCA should be named org.eclipse.rap.internal.gmaps.gmapkit.GMapLCA.

The LCA class itself must have org.eclipse.rwt.lifecycle.AbstractWidgetLCA

as the super class and implement its abstract methods.

We'll just show you a little overview of the methods and their role and then

go further to implement a working LCA for our GMaps widget.

| Method name | Description |

|---|---|

renderInitialization(Widget) |

This method is called to initialize your widget. Normally you will tell RAP which client-side class to use and how it is initialized (think of style bits) |

preserveValues(Widget) |

Here we have to preserve our values so we can see at the end of the lifecycle if something has changes during the process action phase. |

renderChanges(Widget) |

That's the most interesting part. We need to sync the attributes of the widget on the server with the the client-side implementation by sending the changes to the client. |

renderDispose(Widget) |

You can tidy up several things here before the widget gets disposed of on the client. |

After having a brief overview of the principles of the Life Cycle Adapter let's start by implementing the LCA for our GMap widget. After creating the LCA class - which extends AbstractWidgetLCA - we will fill the interesting methods with some logic. First comes the initialization.

public void renderInitialization( Widget widget ) throws IOException {

JSWriter writer = JSWriter.getWriterFor( widget );

String id = WidgetUtil.getId( widget );

writer.newWidget( "org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.GMap", new Object[] { id } );

writer.set( "overflow", "hidden" );

ControlLCAUtil.writeStyleFlags( ( GMap )widget );

}

The JSWriter provides methods to generate JavaScript code that

updates the client-side state of our widget.

Each widget has its own JSWriter instance so that RAP can decide

to which widget the call belongs.

As you can see in the snippet, JSWriter#newWidget is called to create a new widget

on the client side. The second parameters is an array of Objects which are

passed to the constructor of the qooxdoo class (see above).

With JSWriter#set you can easily set different attributes of your qooxdoo object.

Note that there are overloaded methods of set that take care

that JavaScript code is only generated if necessary. That means if a

certain property was left unchanged during the request processing, no JavaScript

code is generated.

The next step is to preserve the relevant properties of our widget. After that

the set-methods from JSWriter can determine whether

it is necessary to actually generate JavaScript code.

As there is only the address property which could change, this

is straight forward.

private static final String PROP_ADDRESS = "address";

public void preserveValues( Widget widget ) {

// Preserve properties that are inherited from Control

ControlLCAUtil.preserveValues( ( Control )widget );

// Preserve the 'address' property

IWidgetAdapter adapter = WidgetUtil.getAdapter( widget );

adapter.preserve( PROP_ADDRESS, ( ( GMap )widget ).getAddress() );

// Only needed for custom variants (theming)

WidgetLCAUtil.preserveCustomVariant( widget );

}

First we use ControlLCAUtil#preserveValues to preserve all

properties that are inherited by Control (tooltip, tabindex,

size, etc.).

So we only need to care about the things implemented in our widget.

We just request a so-called IWidgetAdapter which is responsible for different

aspects in the lifecycle of a widget. In this case we only use it to preserve

the address value

with a predefined key (PROP_ADRESS) to associate it later.

The last line calling preserveCustomVariant is only added for the

sake of completeness.

Variants are a way to have different looks of the same widget and is part of the

theme engine. Please see the Prepare Custom

Widgets for Theming article for further information.

The following step is one of most interesting parts of your lifecycle adapter - the

renderChanges method. As said before it is responsible to write every

change to the outgoing stream which is executed on the client. Let's take a look at the

implementation:

private static final String JS_PROP_ADDRESS = "address";

public void renderChanges( Widget widget ) throws IOException {

GMap gmap = ( GMap )widget;

ControlLCAUtil.writeChanges( gmap );

JSWriter writer = JSWriter.getWriterFor( widget );

writer.set( PROP_ADDRESS, JS_PROP_ADDRESS, gmap.getAddress() );

// only needed for custom variants (theming)

WidgetLCAUtil.writeCustomVariant( widget );

}

Again we use the ControlLCAUtil to write the changes which are implemented on

Control and thus we should not care what's behind it (for those who really want to know it -

it's the same as preserving the values like tooltip, tabindex, size, etc).

Like in the widget initialization we have to render something and therefore we

need to obtain the corresponding JSWriter instance for our widget. We need to use

JSWriter#set to set a specific attribute to the widget instance on the client-side.

There are many different set implementations available for every need. The one used

here is simple: We pass the key for the preserved value to the method so RAP can check if there has

something changed since the last time it was preserved, we pass the name of the client-side attribute

which gets transformed into "set*" and last but not least the value for this setter.

As we can see, the name of the JavaScript attribute (JS_PROP_ADRESS) will call the method

setAdress on the corresponding widget instance on the client. If you wonder where this

method is, take a look at the qooxdoo property system. The address property of our widget will be transformed

by qooxdoo into a set* and get* methods at runtime.

Now we need to process the actions transfered to the server (at least if there are any).

We see in the GMap.js that if the user moves the map a new parameter called

centerLocation will be attached to the current request and transfered to the

server. To read and process it the readData method of the LCA is used.

private static final String PARAM_CENTER = "centerLocation";

public void readData( Widget widget ) {

GMap map = ( GMap )widget;

String location = WidgetLCAUtil.readPropertyValue( map, PARAM_CENTER );

map.setCenterLocation( location );

}

As you can see, it's really easy. You just need to ask the WidgetLCAUtil#readPropertyValue

for the parameter and pass it to the server-side widget implementation. If you wonder why the

center location does not get written in the renderChanges method we implemented above:

This will be your task at the end of the tutorial.

Normally you won't have public methods for attributes which are not changeable programmatically.

For this you would use an adapter or another mechanism to implement the setter behind the scenes.

At the end of the tutorial it is your task hide the public setCenterLocation

method of the GMap widget or - even better - to implement the rendering of

the center location yourself.

The last step is to implement the way our widget is disposed on the client. Normally there is no need to care for anything else and this is also the case with our GMap widget. If you really have to do any other stuff like calling specific methods before the widget is disposed you should do it here.

public void renderDispose( Widget widget ) throws IOException {

JSWriter writer = JSWriter.getWriterFor( widget );

writer.dispose();

}

There are now two additional methods called createResetHandlerCalls and

getTypePoolId. These were introduced by a mechanism that helps to soften the massive

memory consumption on the client. Many of the client-side widgets are not thrown away

anymore, but kept in an object pool for later reuse. Especially with long-running

applications in the Internet Explorer browser, this can make a huge difference. Please

note that this topic is work in progress and, despite extensive

testing, might lead to errors under different circumstances. We recommend not to use this

in your custom widgets.

Loading the client application (with our widget) in a browser will still lead to problems

as nobody knows about the JavaScript resources and where to find them. We can fix this

by using the org.eclipse.rap.ui.resources extension point. We add two new extensions,

one for our custom widget JavaScript file and one for the external JavaScript library of Google

Maps.

<plugin>

<extension

id="org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.gmap"

point="org.eclipse.rap.ui.resources">

<resource class="org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.GMapResource"/>

<resource class="org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.GMapAPIResource"/>

</extension>

</plugin>

Both classes refer to an implementation of org.eclipse.rwt.resources.IResource.

The first one - our custom widget itself - is really easy to implement. We just need to tell

RAP that it is a JavaScript file, where it can find the file and which charset to use. So the

IResource> implementation for the widget JavaScript could look like this:

public class GMapResource implements IResource {

public String getCharset() {

return "UTF-8";

}

public ClassLoader getLoader() {

return this.getClass().getClassLoader();

}

public RegisterOptions getOptions() {

return RegisterOptions.VERSION_AND_COMPRESS;

}

public String getLocation() {

return "org/eclipse/rap/gmaps/GMap.js";

}

public boolean isJSLibrary() {

return true;

}

public boolean isExternal() {

return false;

}

}

For the charset we need to return a string to describe the charset. If you're not sure

you can use of the constants defined in org.eclipse.rwt.internal.util.HTML but be

aware that this is internal. The getOptions method specifies if the file should

be delivered with any special treatment. Possible ways are NONE, VERSION,

COMPRESS and VERSION_AND_COMPRESS. VERSION means that

RAP will append a hash value of the file itself to tell the browser if he should use an already

cached version or reload the file from the server. With the COMPRESS option RAP will

remove all unnecessary stuff like blank lines or comments from the JavaScript file in order

to save bandwidth and parse time.

Remote files like our next task - the Google Maps library - are handled a little bit different.

public class GMapAPIResource implements IResource {

private static final String KEY_SYSTEM_PROPERTY = "org.eclipse.rap.gmaps.key";

// key for localhost rap development on port 9090

private static final String KEY_LOCALHOST

= "ABQIAAAAjE6itH-9WA-8yJZ7sZwmpRQz5JJ2zPi3YI9JDWBFF"

+ "6NSsxhe4BSfeni5VUSx3dQc8mIEknSiG9EwaQ";

private String location;

public String getCharset() {

return "UTF-8";

}

public ClassLoader getLoader() {

return this.getClass().getClassLoader();

}

public RegisterOptions getOptions() {

return RegisterOptions.VERSION;

}

public String getLocation() {

if( location == null ) {

String key = System.getProperty( KEY_SYSTEM_PROPERTY );

if( key == null ) {

key = KEY_LOCALHOST;

}

location = "http://maps.google.com/maps?file=api&v=2&key=" + key;

}

return location;

}

public boolean isJSLibrary() {

return true;

}

public boolean isExternal() {

return true;

}

}

To tell RAP to load external resources we just need to return true in

isExternal. The location should be a valid URL where the resource resides.

In this case it's loaded from the Google Maps server with a special API key. This is specific

for the Google Maps widget and is not needed by other widgets. If you're planning to use

or extend this sample widget we encourage you to get your

own API key for Google as this key

will only work on http://localhost:9090/rap. With every other combination of host, port or

servletName you need to obtain a new key. Additionally we implemented a system property

to define the key without recompiling the widget.

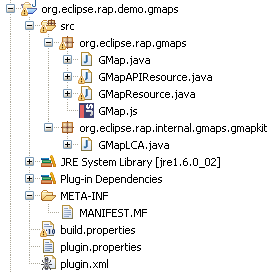

We've just finished our custom widget and our project structure should look like this if we have done everything right.

In order to test the widget we will create a new plug-in project with the following entrypoint:

public class GMapDemo implements IEntryPoint {

public int createUI() {

Display display = new Display();

Shell shell = new Shell( display, SWT.SHELL_TRIM );

shell.setLayout( new FillLayout() );

shell.setText( "GMaps Demo" );

GMap map = new GMap( shell, SWT.NONE );

map.setAddress( "Stephanienstraße 20, Karlsruhe" );

shell.setSize( 300, 300 );

shell.open();

while( !shell.isDisposed() ) {

if( !display.readAndDispatch() ) {

display.sleep();

}

}

return 0;

}

}

Don't forget to add org.eclipse.rap.ui and the GMap widget project as dependencies.

Then we need to register our entry point via the org.eclipse.rap.ui.entrypoint. If

everything went well our demo should look like this after starting the server:

But there was more: the center location we sent to the server. To read it out, we extend the sample with a new button:

public class GMapDemo implements IEntryPoint {

public int createUI() {

Display display = new Display();

final Shell shell = new Shell( display, SWT.SHELL_TRIM );

shell.setLayout( new FillLayout() );

shell.setText( "GMaps Demo" );

GMap map = new GMap( shell, SWT.NONE );

map.setAddress( "Stephanienstraße 20, Karlsruhe" );

Button button = new Button( shell, SWT.PUSH );

button.setText( "Tell me where I am!" );

button.addSelectionListener( new SelectionAdapter() {

public void widgetSelected( SelectionEvent e ) {

String msg = "You are here: " + map.getCenterLocation()

MessageDialog.openInformation( shell, "GMap Demo", msg );

}

} );

shell.setSize( 300, 300 );

shell.open();

while( !shell.isDisposed() ) {

if( !display.readAndDispatch() ) {

display.sleep();

}

}

return 0;

}

}

After a click on the button the current location will be sent to the server (together with the selection event of the button), applied to the widget with the help of our LCA and shown by the MessageDialog. Great!

You completed your first custom widget - congratulations!

Before implementing a heavy custom control we like to give you some tasks to play around

with the GMap widget.

We are delight in seeing what you can do with this little widget. If you have problems, take a look at all the LCAs already provided by RAP. It's not black magic.

Browser-based JavaScript debugging tools such as Firebug can be very helpful.

To enable client debugging, remember to start your application in Debug mode.

This setting preserves the original formatting of the JavaScript code delivered to the client,

whereas it is compressed and obfuscated in the Standard mode.

You can enable the Debug mode directly in the RAP Launcher

(see option Client-side library variant) or by setting the system property

-Dorg.eclipse.rwt.clientLibraryVariant=DEBUG as VM parameter.

You can use the console API to add temporary logging output to your JavaScript

code.